With the Fourteenth Sunday after Trinity we are past the midpoint in Trinitytide: the Teaching Season, the longest season on the Anglican Church Calendar..

The Collect for the day is yet another variation by Archbishop Cranmer from the 1549 Book of Common Prayer based on the Gelasian Sacramentary in the Roman Catholic tradition. As in earlier Collects, this one was modified for the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The key phrase is “faith, hope and charity” in the King James Version and “faith, hope and love” in the New King James Version. The quotation comes from 1st Corinthians 13:1-13, St. Paul’s extended essay on the virtue of love. Nearly all modern translations use the NKJV pattern. The root word is the Latin caritas, reflecting the English academic preference for Latin rather than Greek. The Greek word with the same meaning is agape; however, in the Greek language tradition there are many words which describe different aspects of love; examples: love of fellow man; love of money.

The Epistle reading is again from St. Paul’s letter to the Galatians (Galatians 5:16-24), which is another lesson on Law vs. Spirit and the human emotional struggle with “passions.” St, Paul compares actions which are “fruits of the spirit” (nine actions) to their opposite, “works of the flesh” (seventeen actions). These verses are not easily illustrated and, since there have been several images of St. Paul in earlier posts, I will not include another here.

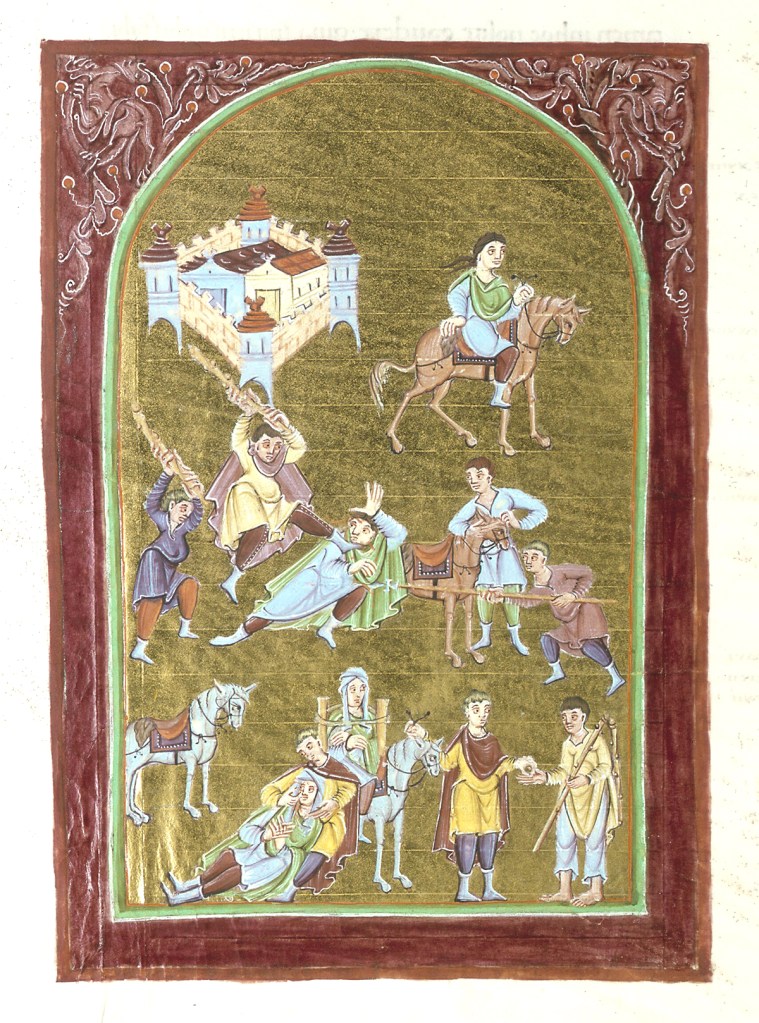

The Gospel reading is the tenth of twelve readings for the season from the pen of St. Luke, Luke 17:11-19, another account unique to the Gospel of Luke, in this case of Jesus’ healing (technically, “cleansing”) of ten lepers at Capernaum. The time is likely around the Spring of 30 A.D. in the third year of Jesus’ public ministry. For this week’s Fr. Ron’s Blog entry I offer you two images, representing two different styles of Scriptural illumination. The first, from the Codex Aureus of Echternach, was prepared in the Byzantine/Spiritual-minded style and includes a word or label which offer viewers a key to understanding St. Luke’s account. The artists present an interpretation of St. Luke’s account in two scenes. The actual healing, or “cleansing,”is presented in the left-hand image, in which all ten men are present. In the right-hand image the artists interpret the return of the one who gave thanks to Jesus (described in verses 15 and 16). I could not enlarge the image without distortion of the very important notation which is painted into the right-hand scene just in front of Jesus’ left hand and directly above the kneeling man who is prostrate at the feet of Jesus. The label is “Samaritan.” In the image, the artists answer Jesus’ question in verse 17: “Were there not ten cleansed? But where are the other nine!” The last of the other nine are shown fading out to the right of the image.

There are two very illuminating details about this account. First, Jesus did not take credit for the healing/cleansing, saying instead to the one who returned and gave thanks: “Your faith has made you well.” Second, as in the Parable of the Good Samaritan (described & illustrated for Thirteenth Sunday after Trinity), it is notable that the one who returned was not one of the Chosen People (expected to do the right thing) but, as the label notes: “Samaritan.” As noted in last week’s Blog posting, I explore the long and troubled relationship between the Hebrew nation and the Samaritans in the text box, Samaria and the Samaritans in the Gospel, found on page 119 in our bookstore publication, The Gospel of Luke: Annotated & Illustrated (available using the link to my Amazon Author Central page and also found at the bottom of the Welcome page of this site and also on the AIC Bookstore page, which offers details about all the AIC Bookstore Publications. Royalties generated by your purchases of these books helps the AIC maintain this site, our Podbean host site and acquire additional images for use in blog posts and other books.

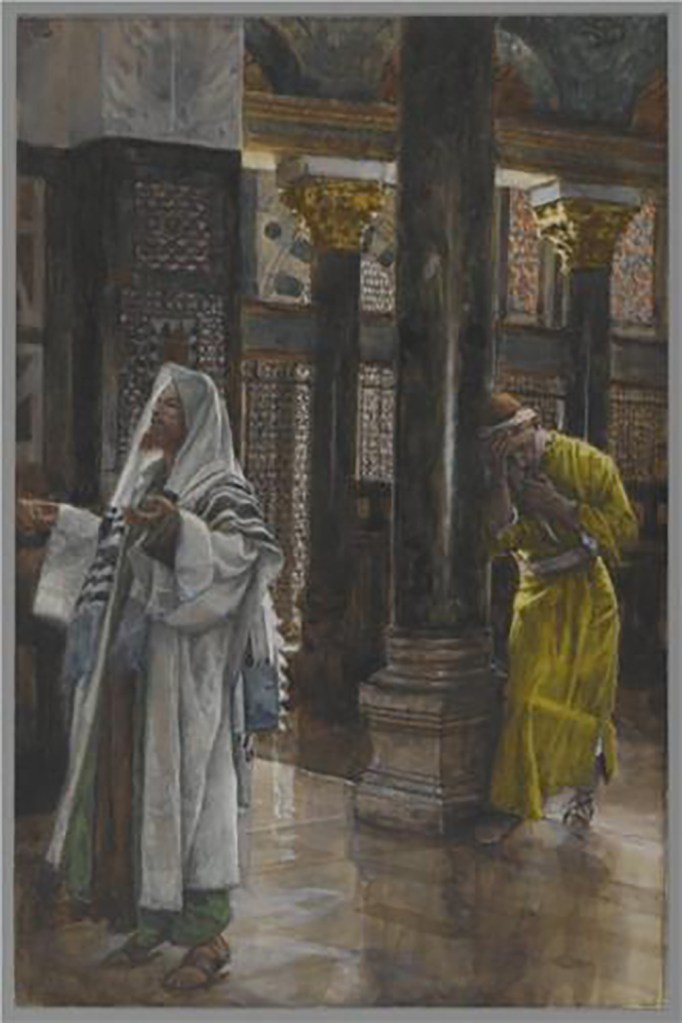

The second image is a watercolor in the historical style painted by French artist James Tissot (born Jacques Tissot, Nantes, France, 1836; died, Chenency-Boilon, France, 1902). The watercolor is part of a collection of Scenes in the Life of Christ which Tissot prepared between 1886 and 1896. The collection was acquired from the artist by the Brooklyn Museum in 1900, adding to its existing collection of art by James Tissot. Other works by Tissot were acquired by the Museum in 1939. The Life of Christ images were photographed by the Museum in 2008 A.D. and later made available for download in digital form. During his preparation for these images Tissot travelled extensively in the Holy Land and nearby regions. Tissot researched both the physical/geographical details but also the manner of dress thought to have been popular in the 1st C., recording his discoveries in the form of sketches of people and places, many of which were used in the watercolors. His work is featured extensively in the AIC Bookstore Publication series on Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John and The Acts of the Apostles. They also are featured in many of our Bible Study and Christian Education Video series. This second image is Illustration No. 87 in The Gospel of Luke: Annotated & Illustrated.

As always, thank you for your interest and support. I invite you to visit the other pages on the site for study materials in print, audio and video formats. Glory be to God for all things! Amen!