Just a little background about the way in which the Anglican Church carries out the mission of Trinitytide as a “Teaching Season,” foll0wed by historic Christian art related to the readings for Second Sunday after Trinity. Just a warning: this may be a little obscure for some readers!

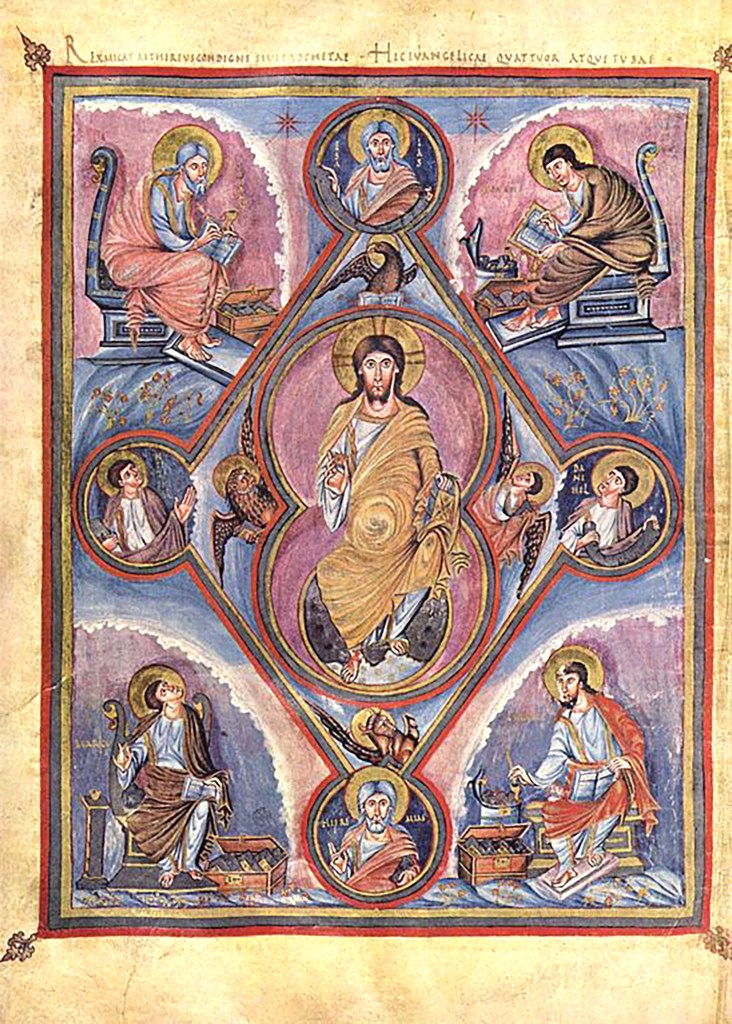

The authors of the Book of Common Prayer, starting with Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the primary auth0r of the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, and the several later Bishops who devised changes in the following centuries, gave the greatest weight to St. Luke’s writings. For this calculation, I have included twenty-nine days, including Whitsunday, Monday and Tuesday in Whitsun Week, Trinity Sunday, the numbered Sundays after Trinity and Sunday Next before Advent. The Gospel of Luke is read 12 times; followed by 9 times for the Gospel of Matthew, 6 times for the Gospel of John, and 2 readings from the Gospel of Mark. The first five Sundays after Trinity feature readings from Luke. This clear bias toward St. Luke reflects the status of the Gospel of Luke as the one Gospel directed toward teaching the beliefs of Christianity to the Gentile world. Both at the beginning, with Whitsunday and the two days in Whitsun Week, Trinity Sunday itself and Sunday Next before Advent, the readings are from the Gospel of John, regarded as the most spiritual-minded of the four Gospels. Seven of the eight readings from St. Matthew’s Gospel are read between Fifteenth Sunday after Trinity and Twenty-fourth Sunday after Trinity.

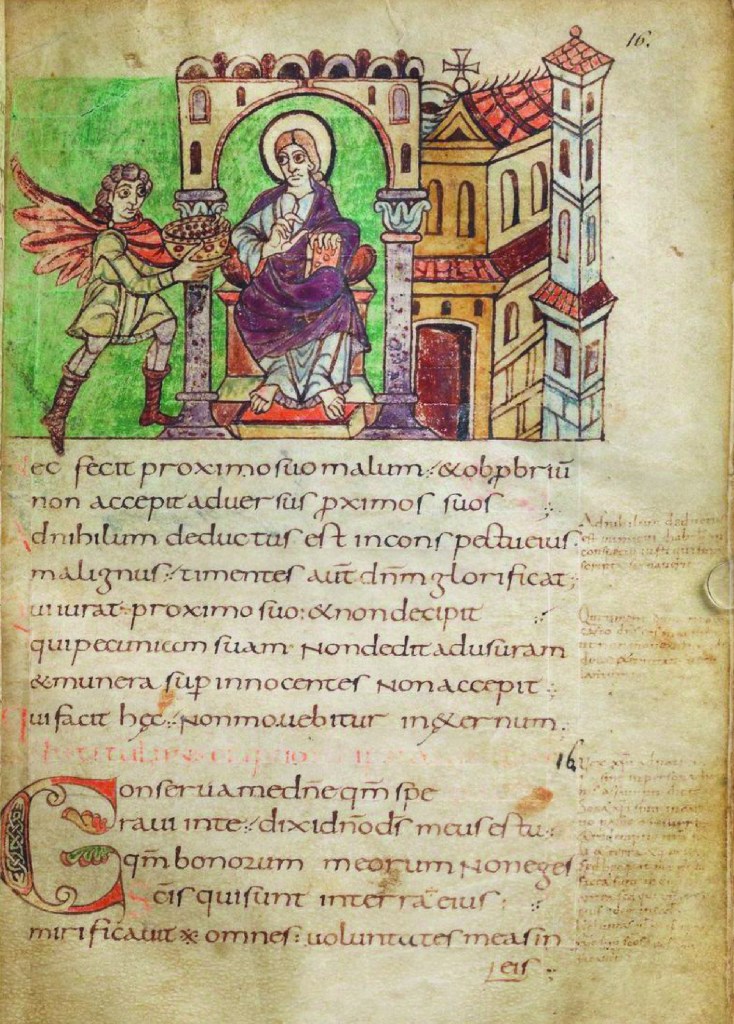

For the Second Sunday after Trinity, the Epistle reading is 1st John 3:13-24, focused on the Christian understanding of “love,” and the Gospel reading is St. Luke’s version of the Parable of the Great Supper (Luke 14:16-24). For this Blog posting, the graphic is not from either of these readings but from the first of the two Psalm readings appointed for the day, Psalm 15. Psalm 15 begins with the question to the Lord, “who shall dwell in thy tabernacle? * or who shall rest upon thy holy hlll?” The early 9th C. artists who illustrated Psalm 15 in the Stuttgart Psalter, made at the Abbey of Saint Germain-des-Pres, near Paris, circa 820 A.D., chose to illustrate a possible answer based on Verses 3, 4, 5 & 6 and the promise made in Verse 7: “Whoso doeth these things* shall never fail.” The illustration is featured on page 36 in the AIC Bookstore Publication, The Prayer Book Psalter: Picture Book Edition.

As always, thank you for your interest and support. Glory be to God for all things! Amen!