Sunday, Nov. 30th, A.D. 2025, marks the start of the penitential season of Advent. My Podcast Homily for First Sunday in Advent is linked from the Digital Library page. The theme is “The Coming of the Light” and in it I discuss Archbishop Cranmer’s new Collect for the occasion, the Epistle reading (Romans 13:8-14) and the Gospel lesson (Matthew 21:10-13). Another Podcast Homily for First Sunday in Advent, this time based on the Morning Prayer readings for the same occasion, is also available. Should you be visual-minded you can watch Episode One (focused on First and Second Sunday in Advent) in our Seasonal Video series, Advent: a Season of Penitence & Preparation. In this video series I also explain other traditions associated with Advent, including the “Greening of the Altar,” the use of Chrismons rather than Christmas ornaments, and the practice of avoiding Christmas carols until Christmas Eve.

For this post for First Sunday in Advent, the highlighted AIC Bookstore Publication is a very special book, Angels: In Scripture, Art & Christian Tradition, which was published in A.D. 2023.

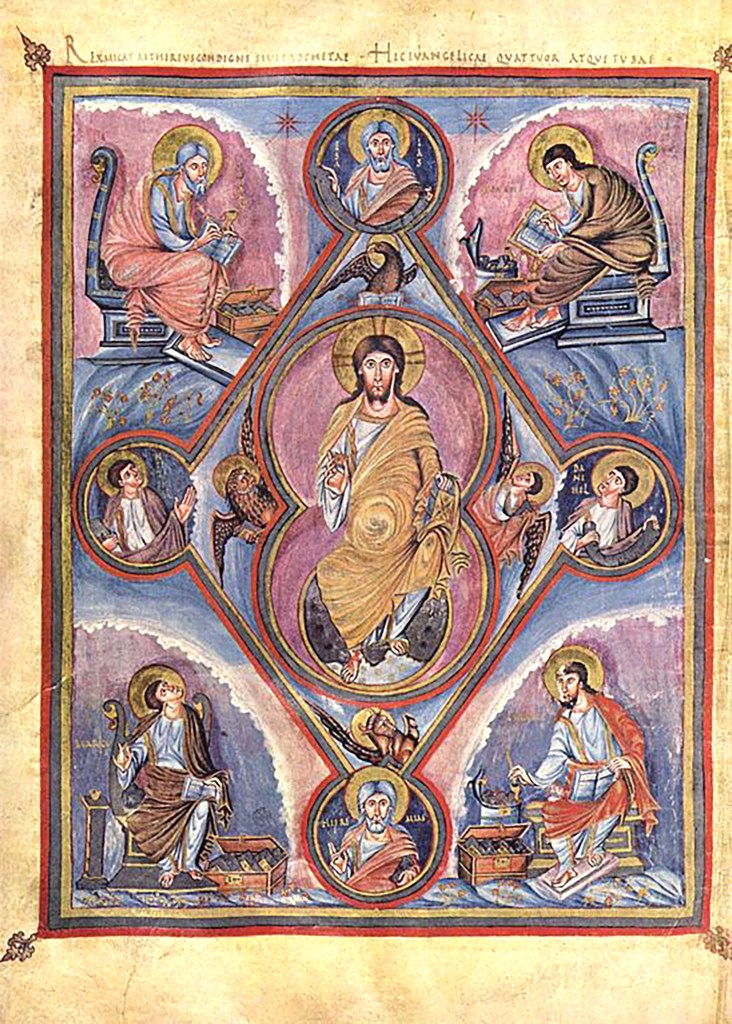

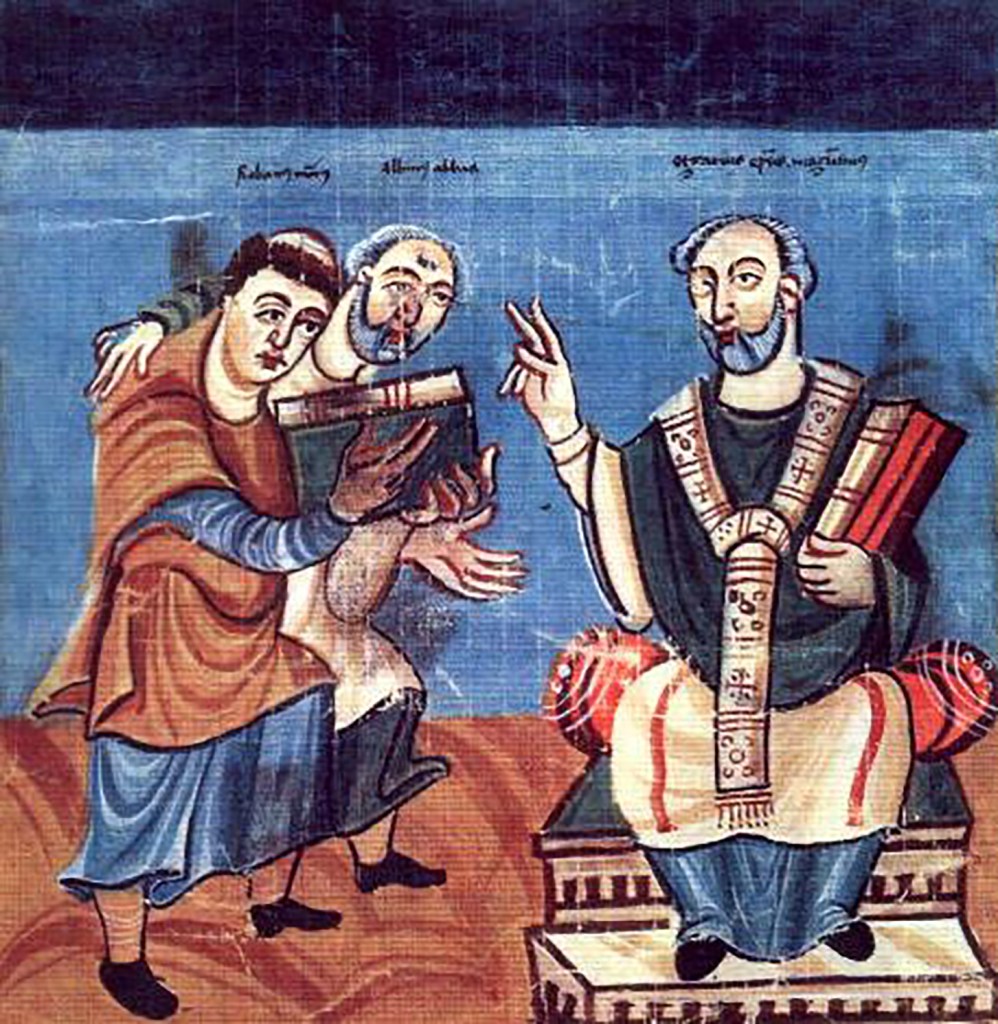

In the Preface to Angels: In Scripture, Art & Christian Tradition I offered this: “The purpose of this book is to educate Christians in the rich literary, artistic and liturgical traditions concerning angels in both the Western and Eastern Church understanding.” In the book I explore every mention of angels in the Old and New Testament, plus the second canon Old Testament and a non-canonical Old Testament book in the Eastern Church tradition. There are 153 illustrations including frescoes, icons, mosaics, stained glass windows, watercolors, paintings and engravings. I pay special tribute to the Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne and his spiritual advisor, the Blessed Alcuin of York; and to the Ottonian and other successors to the title Holy Roman Emperor in the Western Church; to St. John of Damascus, author of the Exact Exposition on the Orthodox Faith, the earliest known explanation of the origin, nature and purpose of angels; and, finally, to St. Clement of Alexandria and St. Thomas Aquinas, the former from the Eastern Church tradition and the latter from the Western Church tradition.

The book is divided into five parts: Part One is a primer on angels); Part Two is focused on every reference to angels in the Old Testament; Part Three includes discussion of each mention of angels in the New Testament; Part Four is focused on references to angels in Christian worship; and Part Five includes discussion and illustrations of angels traditions around the world, including foods and festivities.

The publication of Angels: In Scripture, Art & Christian Tradition completes the planned catalogue of AIC Bookstore Publications. Corkie Shibley suggested the concept of a book on angels. As a special bonus for readers, I have included her recipe for the remarkably light biscuits, which she calls “Angel Biscuits.” The recipe is placed at the end of Part Five.

Royalties on this and the other AIC Bookstore Publications are donated to the AIC. The book is available online through my Amazon Author Central page. Additional information about the catalogue is available on the AIC Bookstore page.

I offer a special thanks to our contributors — and also those who assisted in the production of the book, each of whom is named in the Preface. Contributions and book royalties provide the funds necessary to obtain the high-resolution images and licenses for the use of the same. Through reader support, we have been able to collect and catalogue over 3,000 such images, most of them rarely seen by the general public.

As always, I thank you for your interest and support. Glory be to God for all things! Amen!