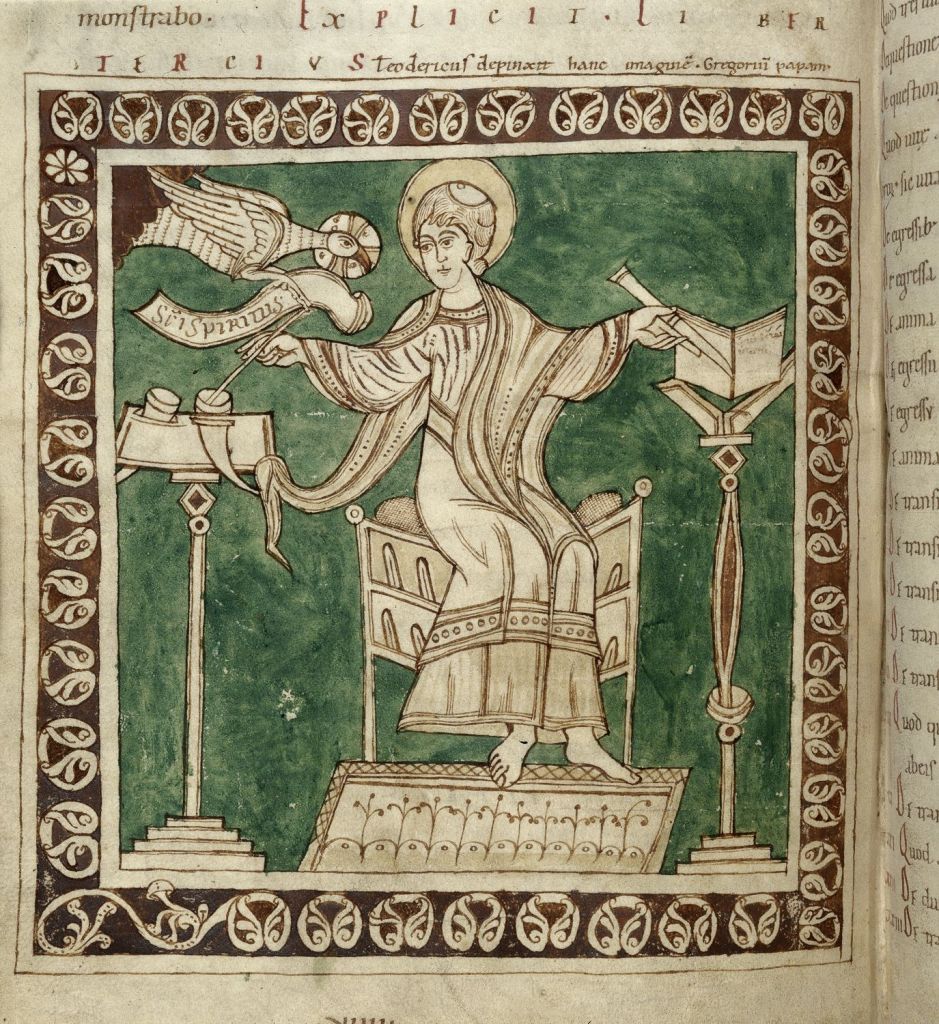

For the Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity the Collect is a composition by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer based upon the Gregorian Sacramentary, named in honor of Pope Gregory the Great, who led the Roman Catholic Church from 590 A.D. until his death in 604 A.D. Illuminations depicting Gregory, acknowledging his profound influence on the liturgy of the Church, often show him with the Holy Spirit whispering into his ear. Note that the word “prevent” has a different meaning than the modern usage. In the 16th-17th C it meant “stand before.”

LORD, we pray thee that thy grace may always prevent and follow us,

and make us continually to be given to all good works; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

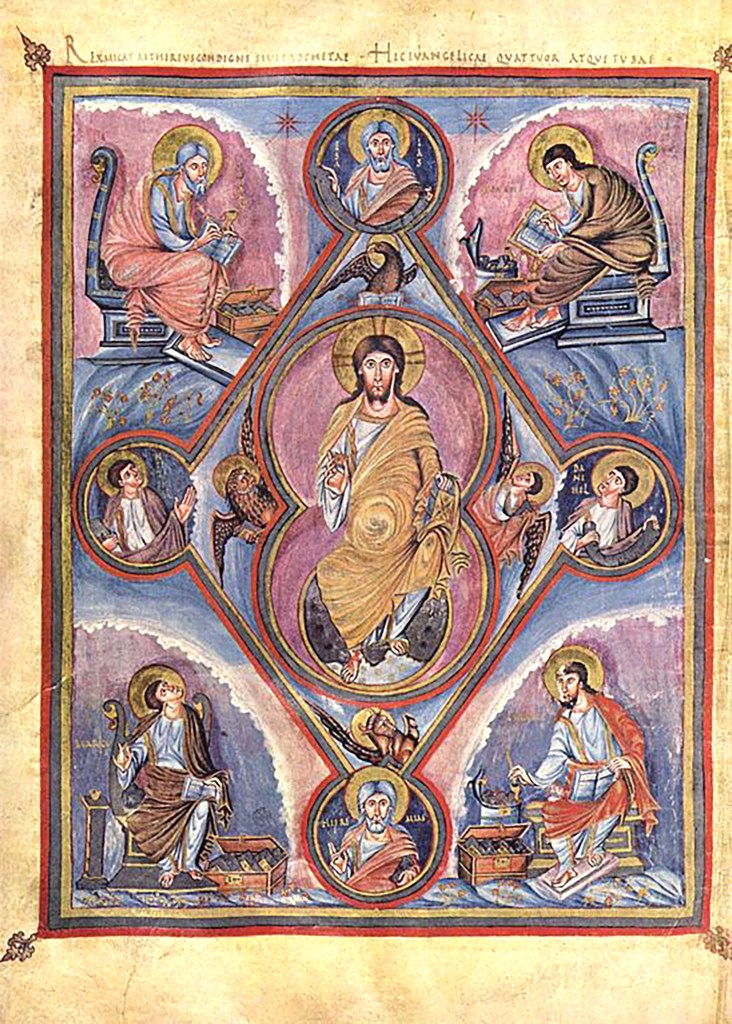

In the Epistle reading, Ephesians 4:1-6, St. Paul also emphases the presence of the Holy Spirit in the faithful in his message concerning the unity of the faith. The reading includes two ic0nic phrases important to St. Paul’s theology: “one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all” and “the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.” The recipient of the letter, the church at Ephesus, was another congregation visited by St. Paul on his second missionary journey (described in Acts 18). According to tradition, St. John served for a time as the functional equivalent of a bishop at Ephesus, where he had taken the Blessed Virgin after the Crucixion. The House of Mary at Ephesus, traditionally said to be the house St. John built for Mary, remains a popular tourist site and is a designated holy place for Roman Catholics. It was visited by three Popes: Paul VI (1967), John Paul II (1979) and Benedict XVI (Nov 2006 during his historic visit to Istanbul (formerly Constantinople) which included celebration of Holy Communion with the Eastern Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch, Bartholomew II.

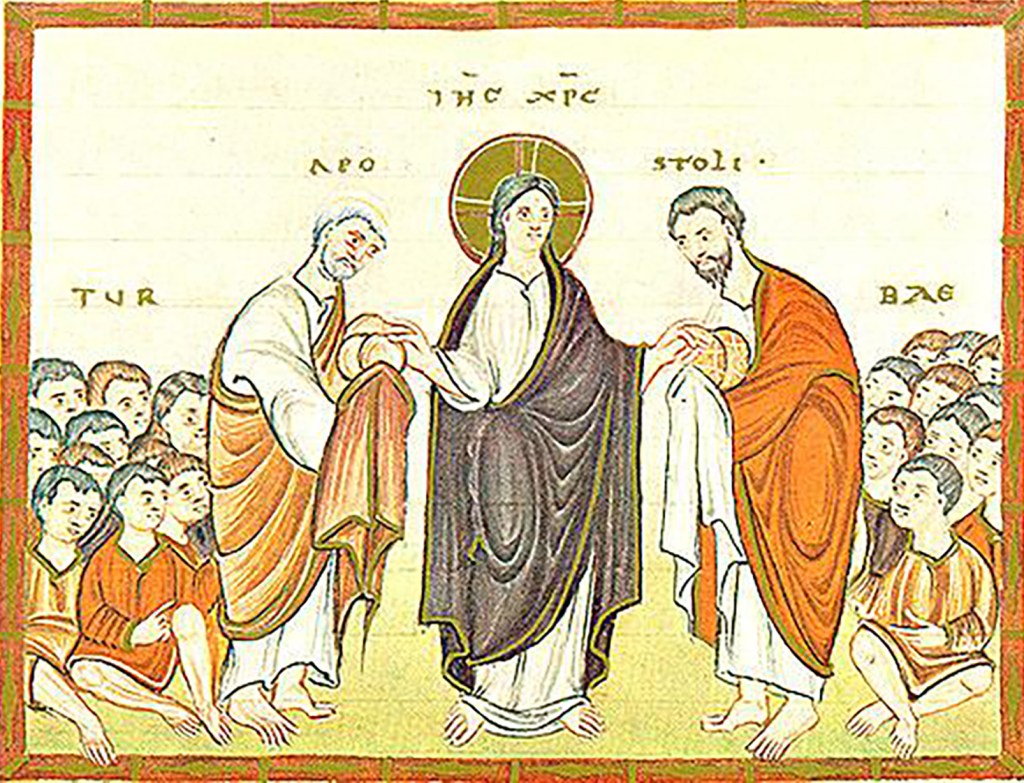

The Gospel reading, Luke 14:1-11, is the twelfth and last reading from St. Luke during Trinitytide: the Teaching Season (in which calculation I include the Sunday next before Advent). All the remaining Gospel readings are from the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of John. The reading includes two separate but related scenes. The first scene simply sets the stage for the second and illustrates the strained relationship between Jesus and the Pharisees. Both scenes, the Healing of the Man with Dropsy and the Parable of the Chief Seats, are unique to the Gospel of Luke. Dropsy, technically known as edema, is a disease which results in extreme fluid retention, usually in the legs and feet. In the mosaic below, the swelling is shown in young man’s lower torso. The mosaic is in the upper walls of the Apse, Monreale Cathedral (Cattedrale di Santa Maria Nuovo de Monreale in Italian). The cathedral was dedicated to the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1182 A.D., eight years after the structure was begun in the reign of the Norman King of Sicily, William II. The full legend above the image is in Latin (only the final three words are visible in the image): “Jesus in domo cujusdam principis fariseorum sanat hydropicum die sabbati” (literally: “Jesus heals the man with dropsy in the house of the leader of the Pharisees on the Sabbath day”). The mosiac, presented in red, white, silver, blue is set into a gold background, with Jesus’ followers at left with two Pharisees and members of the household at right. Look closely at the fine detail in the background buildings and, especially, at the suggestion of flow of the robes of the figures in the foreground. The silver-haired figure, whose face is only partially visible at the left of the image, is consistent with traditional imagery of St. Peter. The halo around Jesus’ head includes the traditional Eastern Church symbology of Christ, always shown with two vertical and two horizontal lines. The “X” above Jesus’ head is a traditional symbol identifying Christ. Every part of the mosaic is made from varying sizes of glass tile. For more details about this ancient method, typical of Byzantine Christian art, see the Fr. Ron’s Blog post, Deesis Mosaic-Hagia Sophia & Other Images, dated April 6, A.D. 2024 (linked from the Archive column at right). In that post I include enlarged sections which reveal more about the “how” of creating mosaics. My Podcast Homily for Seventeenth Sunday after Trinity is linked from the Podcast Homilies page. The readings are discussed in the AIC Christian Education Video series, Trinitytide: the Teaching Season in Episode Seven.

Finally, I offer you one piece of advice for survival in our anti-Christian world of the 21st C. Instead of allowing such thoughts to negatively influence your daily life follow this mantra “Turn it off and tune it out.” The mantra is easy to apply not only to media but also to enterprises which, directly or indirectly, are hostile to the Christian faith. To fill the void, use web resources to create your own list of trusted resources in video, print and electronic and bookmark them for ease of daily use.

As always, thank you for your interest and support. Glory be to God for all things! Amen.