The Sixteenth Sunday after Trinity, celebrated on September 15th in A.D. 2024, marks the first reading from Ephesians during Trinitytide: the Teaching Season. The Collect for the day is another composition by Archbishop Thomas Cranmer made for the 1549 Book of C0mmon Prayer. It is another which was drawn from the “Gelasian” Sacramentary, named after the 5th C. pope although the volume was not published until circa 750. As you have undoubtedly noticed, the Gelasian liturgy, the second oldest in the Roman Catholic tradition, was highly-favored in the English Church both before and after the Church of England separated from the Church of Rome. The word “Church” was substituted for the original “congregation” in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.

O LORD, we beseech thee, let thy continual pity cleanse and defend thy Church;

and, because it cannot continue in safety without thy succour,

preserve it evermore by thy help and goodness; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Epistle reading, Ephesians 3:13-21, as noted above, is the first in Trinitytide from St. Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians, a congregation he established in Asia Minor on his Second Missionary journey. This selection includes St. Paul’s colorful and vivid language which later became popular parts of Christian prayer. These verses are the source of the Christian understanding of the Church as the earthly body of the faithful (as reflected in the previously mentioned insertion of “Church” in place of “congregation”) and the necessity of the Holy Spirit “in” the “inner man” and Christ “dwelling” in the heart (v. 16b-19a). He also uses another term which became part of Christian belief: fulness. I discuss the meaning of “heart” (used 826 times in the King James Version) in the AIC Bookstore Publication, Layman’s Lexicon: a Handbook of Scriptural, Liturgical & Theological Terms, available through my Amazon Author Central page.

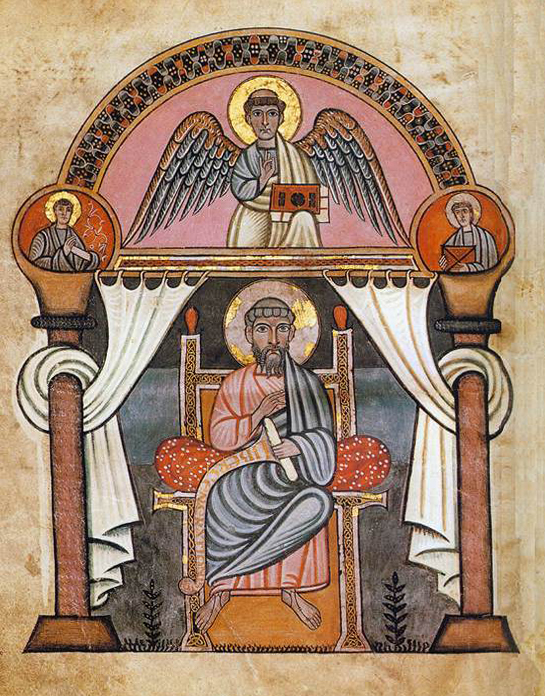

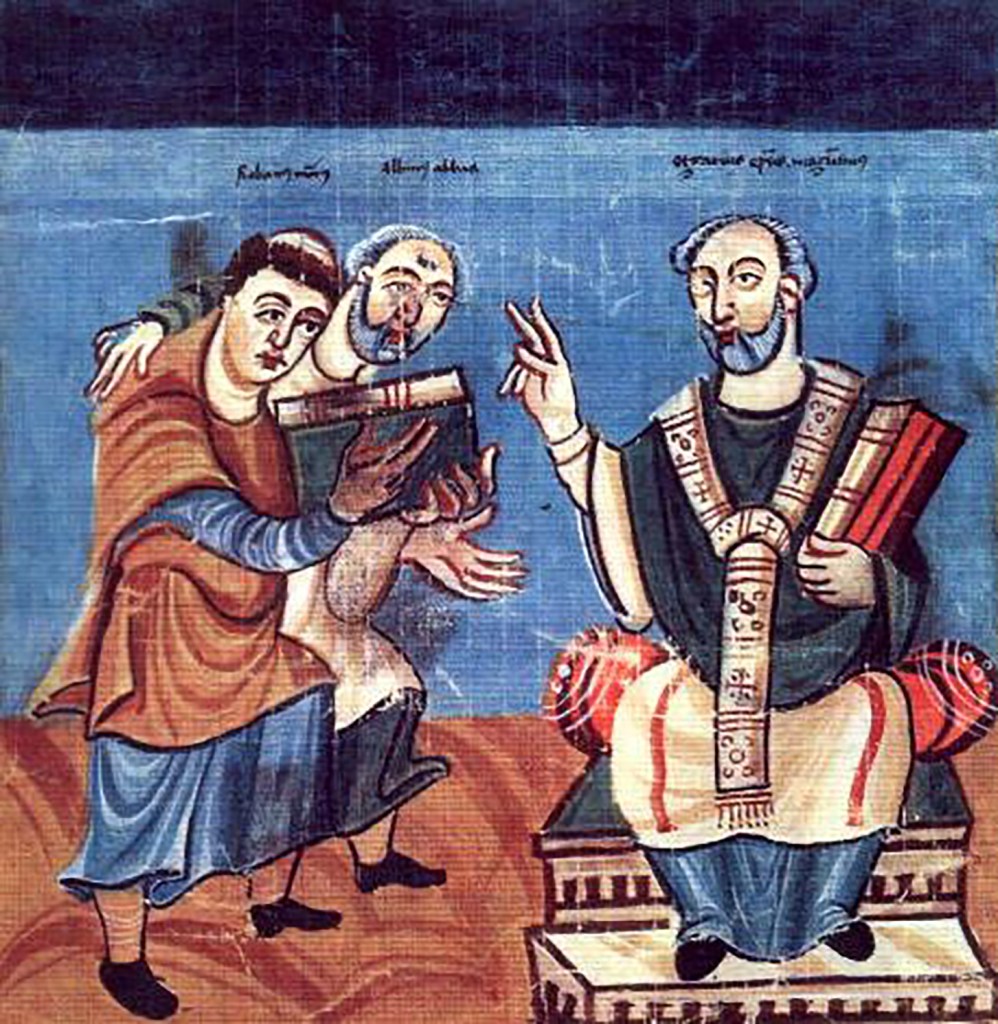

The Gospel reading, Luke 7:11-17, the eleventh reading from Luke’s Gospel in Trinitytide: the Teaching Season, is Luke’s account of Jesus “raising” the son of the Widow of Nain, an event which took place around 28 A.D. in western Judea in the second year of Jesus’ public ministry. Fortunately for Christians, the event was featured often in illuminated Gospels, pericope books and other media. For this post I offer three examples from the AIC’s image archive. The first two, in the spiritual style, are Byzantine/Ottonian illuminations from the late 10th and early 11th C. and the third is an example in the historical style in the form of a last quarter 19th. C. watercolor. All three examples were used in one or more episodes Episode Twenty and Episode Twenty-five in the AIC Bible Study Video series, The New Testament, and in Episode Seven in our Christian Education Video series, Trinitytide: the Teaching Season. The spectacularly detailed image from the Gospels of Otto III was used as Illustration No. 56 in the AIC Bookstore Publication, The Gospel of Luke: Annotated & Illustrated, available through my Amazon Author Central page.

This first example was produced at Reichenau Monastery, Lake Constance, Reichenau, Germany, for Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, whose mother was a Byzantine princess. Using that family connection, artists from Constantinople were brought to Reichenau to aid the already-experienced local artists in producing illustrated Bibles and other liturgical books in the Byzantine style of illumination. During the Ottonian era of Holy Roman Emperors, successors to Charlemagne, coronated at Rome, Christmas Day, 800 A.D., developed their own distinctive style, often labelled after the monk Liuthar, the chief of the artists who began in the Scriptorium at Reichenau around 1000 A.D. The art they produced there remains unequalled in the range of detail, including facial expressions, the use of gold as a background, elaborate foliage and flora patterns as borners (see the example above), and scenes often framed between classical architectural features, such as the columns shown above.

The second example is from the Hitda Codex, an illuminated liturgical book produced for Hitda, the Abbess of Meschede, Germany, circa 1020 A.D. The Codex is the only surviving example of Christian art produced at or near Cologne, the center of the empire created by Charlemagne, a Frankish monarch whose kingdom stretched from the southern half of presentday Denmark into most of Spain, a large part of northern Italy and eastward into the edge of the Balkans. Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor at Rome on Christmas Day, 800 A.D., becoming the first Christian emperor in the West since the Vandals sacked Rome in 455 A.D. In earlier posts, I have explained the important part which Charlemagne and his spiritual advisor, the Blessed Alcuin of York, played in the spread of Christianity into western Europe.

The third and final example is another watercolor created in the historical style by James Tissot, part of his Life of Christ series produced between 1886 and 1896 and now part of the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. In the watercolor, Tissot’s mastery of architectural detail, costume and a wide range of facial expressions is evident, as is his capture of the details of the central scene in St. Luke’s account.

As always, I thank you for your interest and support. Especial thanks is owed to those who have signed on as followers of this Blog. The AIC’s online presence is intended to make these and other amazing examples of Christian more widely available in a variety of media. Most of our material is available free of charge. Author royalties from all the AIC Bookstore Publications are donated to the AIC. I encourage readers/viewers to visit the host sites for all these images, where these and many more are available in the public domain. They are owed a great debt of gratitude for preserving, archiving and, especially, digitizing the original art and making it available for research and education.

Glory be to God for all things! Amen!