Sexagesima Sunday is the second of three pre-Lent Sundays, which are now unique to the Anglican worship tradition. For more historical and other detail on the season watch Episode One in our video series. Gesima: the Pre-Lenten Season or listen to the audio Podcast version, which its linked from the Podcast Archive page. This week I offer site visitors two remarkable examples from our nearly 3000-item library of historic art.

The Collect for Sexagesima Sunday was adapted by Archbishop Cranmer from the Gregorian Sacramentary, which was also the source for the Collect for Septuagesima Sunday. It was used for the first time in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer and was read by Archbishop Cranmer himself on Whitsunday/Pentecost, June 9, A.D. 1549. The prayer book also may have been used earlier in the same year at St. Paul’s Cathedral, London. Like the Epistle and Gospel reading for the day, the themes are the “mercies” of God and the Christian virtues. Sexagesima Sunday is actually 57 days before Easter and not the sixty which its name suggests. Readers should remember that the Greek word for God, Theos, (Strong’s Greek Word #2316) is often translated as The One Who Sees.

O LORD God, who sees that we put not our trust in any thing that we do;

Mercifully grant that by thy power we may be defended against all adversity;

through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

The Epistle reading, 2nd Corinthians 11:13-21, St. Paul’s letter to the formerly pagan congregation he established at Corinth on his Second Missionary Journey accompanied by Silas. The verses are discussed and illustrated in Episode Two of our video series, Gesima: the Pre-Lenten Season, linked from the Digital Library page and in audio form from the Podcast Homilies page. In this epistle to congregation most resistant to his teachings, he mentions the Christian virtue of diligence and names forms of suffering he endured on his journey, including stoning, beatings, shipwreck, followed by a list of more general adversities, including hunger, thirst and robbery. The image of St. Paul was painted by one of the world’s most gifted icon painters. As the credit line suggests, the image is no longer mounted in the church for which it was being made, having become an “historic” object rather than a religious one. Even in its unfinished form it is an exceptional example of art put to use for Christian purposes. Frequent visitors to this site may have noticed that another image of this icon has a blue background, which was the result of studio lighting. This one is the real thing and will be used in all future AIC Publications and updates to existing books and videos.

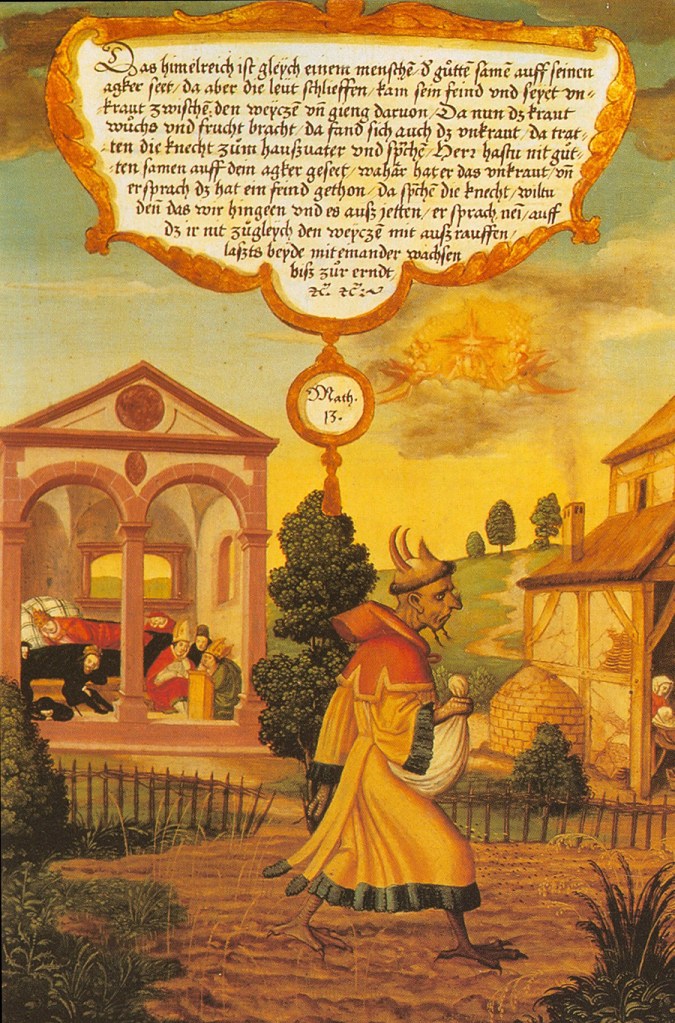

The Gospel reading, Luke 8:4-15, is the evangelist’s account of the Parable of the Sower. The watercolor above appears as Illustration No. 71 in our publication, The Gospel of Matthew: Annotated and Illustrated and Illustration 71 in The Gospel of Mark: Annotated and Illustrated. In the comparable volume on the Gospel of Luke I used an oil on canvas by Vincent Van Gogh. These books are available through my Amazon Author Central page. A summary of the book, including price and pagination, is found on the AIC Bookstore page. The image is from a collection of around 300 images in James Tissot’s Life of Christ series, the largest collection of which is now held at the Brooklyn Museum.

As noted in previous posts late last year, I am working on Episode Six and Episode Seven in our video series, The War on Christianity. I expect to finish the text and slides before the end of this weekend. Each of the 24 slides in Episode Six and 33 in Episode Seven is produced by clipping from a sheet with six slides each and some single image pages in Adobe Photoshop. Afterward, each slide must be inset into a video and the sound track recorded using Apple’s iMovie software. The completed episodes probably will not be ready for publication before the middle to the end of March. It will be linked from the Digital Library page and the voice track, converted into an MP3 file, linked from the Podcast Archive page. In other news, I’ve had.a request from an Anglican clergyman in northern Italy to use some material from this site. I have given permission with the condition that the material contains a link to this site.

As always, thank you for your interest and support. Glory be to God for all things! Amen!