First, I must apologize for last week’s error in the readings for Twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity, when the Collect, Epistle and Gospel readings should have been the same as the Sixth Sunday after Epiphany instead of the Fifth Sunday after Trinity.

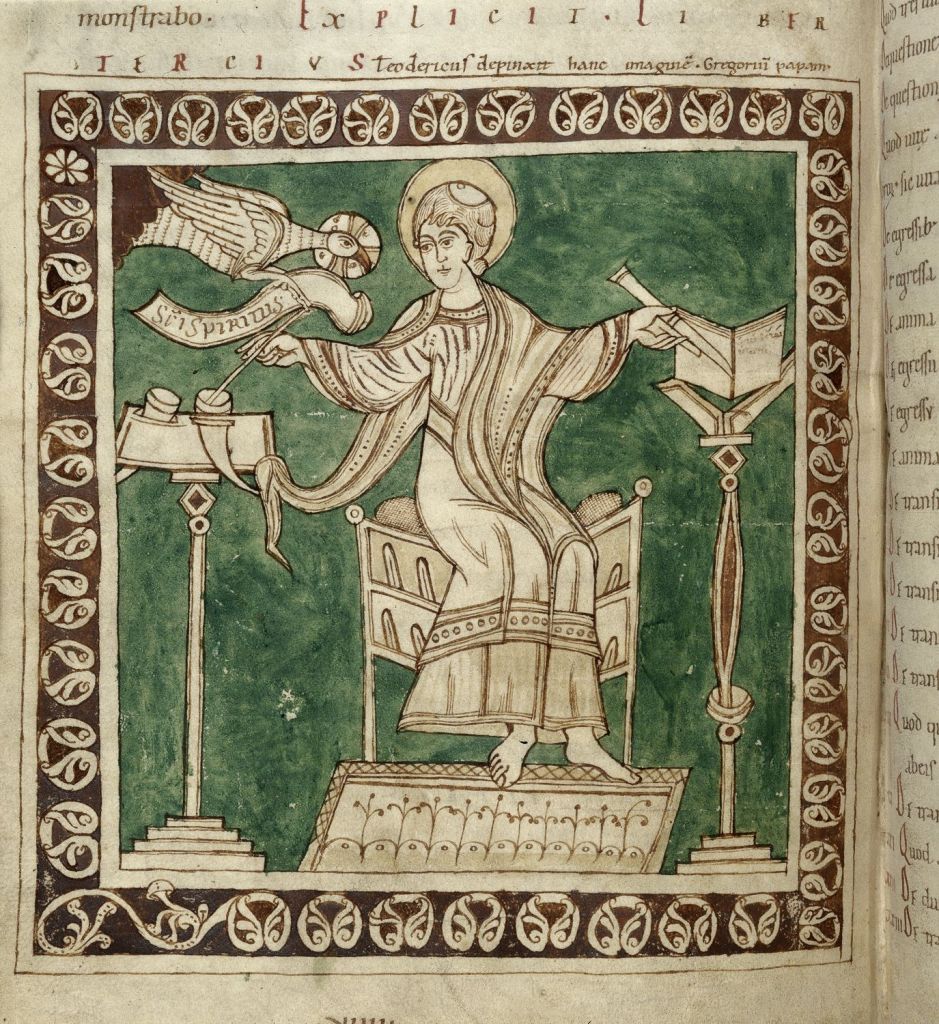

Trinitytide, the longest season on the Anglican Church Calendar, finally comes to an end with Sunday Next before Advent. In the 1892 Book of Common Prayer the occasion was labelled Twenty-fifth Sunday after Trinity. It is commonly known as “Stir-up Sunday,” a label based upon Archbishop Cranmer’s adaptation of a “Daily” prayer from the Gregorian Sacramentary as the Collect for the Day. Church historians suggest that the “stir up” phrase in the Gregorian prayers was inspired by the writings of the Apostles Paul (2 Timothy 1:6) and Peter (2 Peter 1:13; 3:1).

STIR up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people;

that they, plenteously bringing forth the fruit of good works,

may by thee be plenteously rewarded; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

For Sunday Next before Advent, the first reading, known as a “for the Epistle” reading, is Jeremiah 23:5-8, a prophecy of the coming of a “righteous Branch” in the line of descent from King David and under whom the people are promised “judgment and justice in the earth.” The prophecy uses all capital letters in the spelling of prophesied Messiah: THE LORD OF OUR RIGHTEOUSNESS. Verse 5 is read as the Second Chapter (of three) in the traditional Anglican prayers for Third Hour in the AIC Bookstore Publication, Hear Us, O Lord: Daily Prayers for the Laity, available through my Amazon Author Central page.

The Gospel reading, John 6:5-14, is the evangelist’s account of the miraculous Feeding of the 5,000, which in extended form (using verses 1-14) is also the reading for Fourth Sunday in Lent. It is illustrated here in one of James Tissot’s historical style watercolors in which the artist captures the enormous scale of the event with details of the audience and the local geography.

As always, thank you for your interest and support. Glory be to God for all things! Amen!