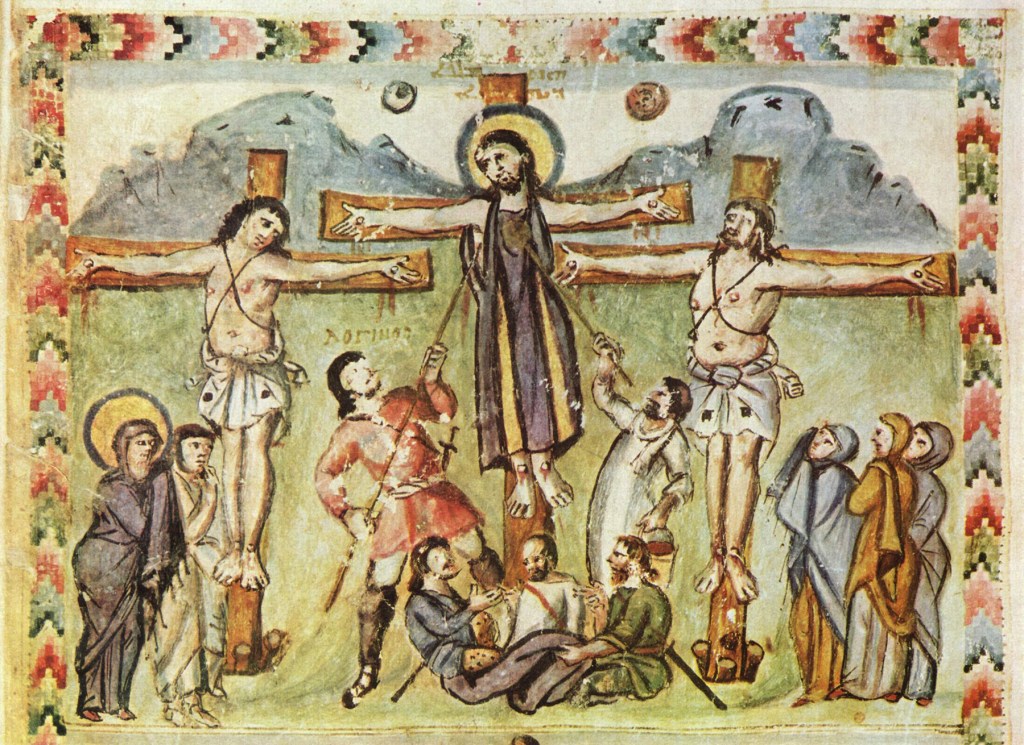

This week I continue my discussion about Liturgical Worship in the Anglican tradition using the 1928 Book of Common Prayer. The illustration below shows clergy officiating at Holy Communion using the Sarum Rite. Sarum is modern day Salisbury, England. The Sarum Rite in England is a predecessor of the 1549 Book of Common Prayer, the first England language liturgical prayer book produced under the supervision of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

One of the best commentaries on the 1928 Book of Common Prayer was written by Massey Shepherd. It includes an introductory commentary plus section-by-section commentary on the entire BCP. On the Holy Communion liturgy, pages 67-89, he observes that the words to be spoken by clergy and people before an after the Gospel reading (“Glory be to thee, O Lord” and “Praise be to thee, O Christ”) are “a reminder that liturgical worship is a corporate action of both minister and congregation, conducted under the inspirational judgment of the Lord.”

Shepherd also notes that the Sanctus prayer, spoken during the Preface, is a paraphrase which is derived from the prophet Isaiah’s vision of the heavenly throne, in which the seraphim sing (Isaiah 6:1-3). Holy, holy, holy, Lord God of hosts, Heaven and earth are full of thy glory: Glory be to thee, O Lord most high.”

Another interesting observation by Massey Shepherd concerns the opening words of the Prayer for the Whole State of Christ’s Church (BCP p. 74) is evidence of the Church’s acceptance of the understanding that God listens of the prayers/petitions of His faithful people and, further, that the text affirms that the people/congregation, in hearing the remainder of the prayer, acknowledge the obligation to be obedient unto His divine will: “all those who do confess thy holy Name may agree in the truth of thy holy Word, and live in unity and godly love.” This understanding is more directly addressed in the preface to the General Confession (p. 75).

As always, thank you for your interest and support. Glory be to God in all things! Amen!